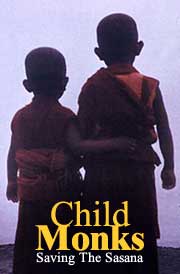

- Of Child Ordination and

the Rights of Children

- The Associated Newspapers

of Ceylon

-

Colombo -- At the

outset, I must state that I appreciate Dr. Obeysekere bringing out into the open a topic,

which would be regarded in many circles as taboo but is worth 'airing'.

Dr. Obeysekere says in his article,

"my concern here is with the whole problem of child monks because this seems to be a

violation of both the letter and the spirit of Theravada Vinaya ..."

Dr. Obeysekere says in his article,

"my concern here is with the whole problem of child monks because this seems to be a

violation of both the letter and the spirit of Theravada Vinaya ..."

But I would like to ask the question

"how so?"

The rule that a boy has to be fifteen

years to "go forth" (pabbaja, which is different from upasampada or higher

ordination) was qualified by another rule, which Obeysekere cites, viz., "I allow

you, monks, to let a youth of less than fifteen years of age and who is a scarer of crows

to "go forth". (Vin. 1.79) Obeysekere says that unlike the former rule, the

latter "is so vague that it simply cannot be applied to our times". I do not

agree. The Vinaya atthakatha (commentary) 1003, explains the word uttepeti as "having

taken a clod of earth in his left hand, he is able, sitting down and having made the

crow's fly up (kake uddapetva) to eat a meal put down in front of (him)'. It has a simple

explanation unlike some dark, mysterious and incomprehensible element in a Gothic Tale. It

must surely mean that the boy can look after himself and does not need a "baby

sitter", so to speak.

In this connection, I remember a radio

feature recorded by the late Lala Adittiya in the 1970's, which described how a farmer in

Sri Lanka had employed children to chase away birds from a field of ripening grain. The

actualities recorded on tape included the noise made by children clapping their hands

together and shouting. This is a fairly common sight even today in rural areas, I am told.

Lala certainly witnessed that scene in Haputale in the 70's. Does this not indicate that

we have here an example of a practice that existed in the Buddha's time which still exists

in our part of the world?

Another Vinaya rule was laid down with

regard to children "going forth" when king Suddhodhana expressed a parent's and

a grand parent's heartfelt sorrow at a child or grand child renouncing household life. The

Buddha, taking his words into consideration, formulated the following rule: "Monks, a

child who has not his parents consent should not be allowed to go forth ..." So then,

this is the criterion with regard to a child's pabbaja. The parents' consent is vital. The

rule does not specify a particular age but it is a direct outcome of king Suddhodana's

request with regard to Rahula's "going forth" at 7 years. (Vin. 1.83)

It is most enlightening to see what

prompted that formulation of the exception to the earlier quoted rule of not allowing boys

under fifteen to "go forth". It is stated in the story connected to the rule

that a family, which was supporting Ven. Ananda, died of malaria and only two young boys

survived. These two boys on seeing monks going on their alms round ran up to the monks

only to be told to go away. Whereupon they began to cry. Ven. Ananda, ever compassionate

as always, having observed this scene and being deeply concerned that "they should

not be lost, "kena nu kho upayena ime daraka na vinasseyyun ti" (now by what

means might these boys not be lost?) reported the matter to the Buddha who then inquired

"But, Ananda, can they even chase crows?" On receiving the answer to the

affirmative, he then gave permission to let them "go forth" and formulated the

exception to the earlier rule. We see then that the motive originated in compassion for

the two-orphaned boys. This, then, is what should be taken in to account.

As a young socio-anthropologist told me

"Giving a child to a temple is a coping mechanism of the poor Buddhists of Sri Lanka,

Burma, Thailand and Cambodia. By letting children "go forth", parents also hope

that the child will grow up in a disciplined, spiritually refined environment and to a

great extent their expectations are met.

From the child's point of view, senior

monks are often lenient with young Samanera monks. They are allowed to play with other

little boys of the village, within the temple premises. Vinaya rules, which apply to

Samanera monks, consist of only ten whereas for fully ordained monks there are 220.

Upbringing in a very poor family falls

short of the ideal, for parents are too pre-occupied with the material aspect of the

survival of their, too often, large families and neglect the "bringing up"

process of the child. In a temple environment, a child is benefited by having not only

food, clothing and shelter but a certain degree of discipline, guidance and education

also. Even Obeysekere admits in his article "... in general village monks are morally

responsible human beings".

I would like to quote a few statistics,

which reveal a very grim picture of the ills which poverty breeds in our country. The

following figures are not certified but have been roughly estimated by Child Rights groups

and organisations working in this field. It is said one hundred thousand children are

employed as domestic labour. Thirty to fifty thousand comprise sexually abused children

and of these five thousand are acknowledged to being sold into sexual activity. 51% of

Colombo's population live in shanty towns which are cess pools of vice - drug addiction,

alcoholism, child abuse and prostitution. Compared to this sordid scenario, a Buddhist

monastery must seem like a haven.

Of course, prospective Samanera monks do

not come always from the "poorest of the poor". During the Buddha's time, the

Sangha was an elitist organization. Its members were drawn from the upper classes and even

royalty, though the poor and downtrodden were not debarred from entering the Sangha. It

was so even in Sri Lanka.

The socio-anthropologist I spoke to does

not think that the "going forth" of children should be politicised but families

allowed to give children to the temple, as is the age-old custom. It is preferable if the

child is of an age to decide for himself whether he would like to enter the monastic life

or not but she thinks it is far better than the alternative of a child having to enter the

labour market which would kill his childhood and blight his future as an adult.

The incidence of child abuse (if any) in

Buddhist monasteries is not known. There are no statistics. Of course, a Samanera monk can

leave the Order any time if he finds the temple atmosphere unpleasant. He is not trapped

in a hopeless situation.

Dr. Obeysekera observes that with regard

to child abuse in monasteries, "one ought to have institutional safeguards ..."

As a matter of fact, there are very comprehensive Vinaya rules that cover every

conceivable type of activity, which contravenes or is detrimental to the Brahmacariya life

of the monastery. They range from major Parajika offences, the result of which is

expulsion from the Order, to Sanghadisesa offences which are very grave and which

necessitate the convening of a special assembly of the Sangha for the purpose of deciding

what action should be taken. There are also 92 Pacittiya rules of lesser magnitude for

which punishments and penalties are prescribed. There are 75 Sekhya rules and several

other rules, which need not be mentioned here. The Vinaya machinery exists and the rules

are framed in a very legalistic manner. Even producers for instituting action, known as

adhikaranasamatha exist.

To my mind, the answer to child abuse,

which may or may not exist in Buddhist monasteries, is not closing the doors to young

prospective monks and allowing only senior citizens to enter its portals to lead the good

life but to urge the Sangha to activate the already existing Vinaya machinery (if it is

not being done) and to hold the fortnightly Patimokkha regularly in all monasteries or

each monastic community within its sima, if that ceremony has fallen into disuse.

If a monk's conduct is not what it should

be, lay supporters have every right ot criticize him, as it has been recorded in the

Vinaya texts. The Vinaya rules have much to do with conduct which should accord well with

what is expected of monks by the wider society.

Another point I would like to mention is

that it is because of the kind of materialist society we live in that we tend to look upon

monastic life as something weird for a child or suitable only for the "poorest of the

poor". If the custom of children "going forth" were not existing, scholarly

disciplined monks of the calibre of Ven. Balangoda Ananda Metteyya, Ven. Talalle

Dhammananda, Ven. Madihe Pannasiha, Ven. Rerukane Chandavimala, Ven. Hikkaduwe Sri

Sumangala and a host of such monks would have been probably lost to us. Ven. Dr.

Kamburupitiye Vanaratana has pointed out in an interview published in the book .....Take

Sinhala ........ written by Ven. Itthapane Dhammalankara Thera that the present system of

recruiting Samanera monks is not satisfactory, as very often the candidate's suitability

is not gone into. During his time this was done. The Ven. Thera himself had to wait 8

months in the temple until he was considered suitably qualified to become a novice monk. A

basic educational background and a good knowledge of the Sinhala language and literature

were thought essential.

I do not think that the venerable

prelates mentioned above were particularly unhappy in their temple environments as

children. In fact, the close reverential tie a novice monk develops for his upajjhaya

(preceptor) monk, I am told, is very much akin to the father-son relationship in a lay

family. At Vin. 1.45 it is laid down in detail the duties of a preceptor monk towards his

pupil-monk and vice versa. The following excerpt will give an idea:

"Monks, I allow a preceptor. The

preceptor, monks, should arouse in the one who shares his cell the attitude of a son; the

one who shares his cell should arouse in the preceptor the attitude of a father ..."

Thus the letter and the spirit of the Vinaya obviate any kind of child abuse or child

exploitation.

The bond that exists between the

preceptor monk and his pupil monk is very strong. It has kept the continuity of the

monastic tradition going on from generation to generation. When the senior monk advances

in years, it is his pupil who looks after him like a loving child with gratitude for the

long hours of teaching and training bestowed on him, not only with regard to the pupil

monk's studies but the moulding of his character as well. The strong family feeling in a

monastic community cannot be stressed enough. It must be mentioned here that moulding the

character of a young Samanera monk is much easier than moulding the character of a 15 year

old in today's context with the kind of evils and sensory attractions there in the

society. Television and other media certainly do not promote the life of contentment with

few wants.

It should also be mentioned that Samanera

monks who are given a Pirivena education do have to study Pali, Sanskrit and Buddhism

besides other subjects. Very often, they specialize in Buddhist studies at university and

at Post Graduate level. Many of them may leave the robes after receiving a university

education but the individual is all the richer for having spent time in a temple.

Something of the refining and disciplining atmosphere does rub off on him. To counter

balance those who disrobe, there is always a handful that will remain. The custom of

recruiting children for the Sangha on a selective basis will ensure that remaining

balance, whereas if the custom is discouraged it might be tantamount to dealing a fatal

blow to the monastic establishment itself.

The view that abandoning household life

is best suited to senior citizens was a way of thinking that existed also in the Brahmanic

tradition of the four stations in life called the catur asrama dharma. But Buddhism made

renunciation valid even for a young adult. Perceiving the cause of dukkha and consequently

wishing to practise the path leading out of it cannot be circumscribed to a particular age

group.

Materialism has somewhat veiled these

perceptions but the wellsprings of Buddhism in this country have not dried up completely

yet. Perhaps we should take a leaf out of our neighbouring Buddhist countries and have

temporary ordination of youths. Let us try and see how the good aspects of our monastic

institution may be preserved instead of throwing out the baby with the bath water.